-

In the annals of American financial history, few institutions loom as large—or as controversial—as the Federal Reserve System. Often simply called “the Fed,” this central banking powerhouse was born not in the marble halls of Washington, D.C., but amid the misty shores of Georgia’s Jekyll Island.

As Atlantans, we take a certain local pride in this pivotal chapter, even as it raises uncomfortable questions about secrecy, power, and economic control.

This article delves into the turbulent conditions that preceded the Fed’s creation, the shadowy origins right here in our state, and the far-reaching ramifications that continue to shape our economy today.

The Precarious Financial Landscape Before the Fed

To understand why the Federal Reserve was deemed necessary, we must rewind to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a time when America’s banking system was a patchwork of instability.

Without a central bank, the U.S. relied on a decentralized network of national and state banks, backed by the gold standard but plagued by frequent panics and runs on deposits.

America on the Brink: A Nation Held Hostage by Bank Panics

Before 1913, America’s money system was a ticking time bomb. Bank runs weren’t rare – they were routine. One rumor, one bad harvest, one Wall Street gamble gone wrong, and entire towns watched their life savings vanish overnight.The Panic of 1907 was the final straw.

Stock market crashed 50%. Banks boarded up their doors. Grown men fought in the streets to withdraw cash that no longer existed. The entire system teetered on the edge of total collapse.

The message was clear: the United States of America had no control over its own money.

The Panic of 1907 — the first global financial crisis of the 19th century — stands out as the catalyst. Triggered by a failed speculative bid to corner the market on United Copper Company stock, it led to widespread bank failures, stock market crashes, and economic turmoil.

“The immediate trigger of the panic was a failed effort by a group of speculators to corner the stock of the United Copper Company,” former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke said in a speech on the subject. “The main perpetrators of the failed scheme, F. Augustus Heinze and C.F. Morse, had extensive connections with a number of leading financial institutions in New York City. When the news of the failed speculation broke, depositor fears about the health of those institutions led to a series of runs on banks, including a bank at which Heinze served as president.”

In New York, trust companies—unregulated entities similar to banks—faced massive withdrawals, forcing closures and sparking contagion across the country. J.P. Morgan, the era’s most powerful financier, personally intervened by pooling funds from wealthy bankers to bail out failing institutions, averting total collapse.

But this ad-hoc rescue highlighted a glaring vulnerability: the U.S. had no formal mechanism to provide liquidity during crises, no lender of last resort.

Prior panics in 1873, 1893, and others had exposed similar flaws.

Currency was inelastic, meaning it couldn’t expand or contract with economic needs—farmers in the agrarian South, including Georgia, often suffered from tight money supplies during harvest seasons, leading to deflation and debt burdens.

Regional disparities were stark; Southern banks, still recovering from the Civil War, were particularly underserved. Calls for reform grew louder, with populists like William Jennings Bryan advocating for “free silver” to inflate the currency, while bankers pushed for a more stable, centralized system.

By 1910, the stage was set for change. The Aldrich-Vreeland Act of 1908 provided temporary emergency currency, but it was a stopgap. Influential figures, including Senator Nelson Aldrich of Rhode Island—chairman of the National Monetary Commission—recognized the need for a permanent solution. Yet, public distrust of “money trusts” and big banks made open reform politically risky.

The Secret Birth on Jekyll Island

Enter Georgia’s Jekyll Island, a secluded barrier island off the coast near Brunswick, once a winter retreat for America’s elite like the Rockefellers and Vanderbilts. In November 1910, under the cover of a fabricated “duck hunting trip,” a group of six powerful men convened at the Jekyll Island Club to draft what would become the blueprint for the Federal Reserve.

Led by Senator Aldrich, the attendees included Paul Warburg (a German-born banker from Kuhn, Loeb & Co.), Frank Vanderlip (president of National City Bank), Henry Davison (a J.P. Morgan partner), Charles Norton (president of First National Bank of New York), and Benjamin Strong (another Morgan associate). Abraham Piatt Andrew, assistant secretary of the Treasury, rounded out the group.

They arrived incognito, using first names only to avoid detection, as any whiff of a “bankers’ conspiracy” could derail their efforts. Over 10 days, they hammered out the “Aldrich Plan,” proposing a central bank controlled by private bankers with regional branches to manage currency and credit.

This was no altruistic endeavor; the men represented institutions holding about one-fourth of the world’s wealth. Their goal: Stabilize banking while preserving private influence, countering populist demands for government control.

The plan faced opposition. Progressives like Congressman Charles Lindbergh Sr. decried it as a “money trust” scheme. After revisions to appease Democrats—renaming it the Federal Reserve Act, adding presidential appointments, and creating 12 regional banks—it passed Congress in 1913.

President Woodrow Wilson signed it on December 23, 1913, and the system became operational in 1914, with Atlanta hosting one of the regional Federal Reserve Banks (District 6), a nod to Southern economic needs.

Why Georgia? Jekyll Island’s isolation ensured secrecy, allowing frank discussions away from prying eyes. As Warburg later wrote, “The results of the conference were entirely confidential. Even the fact that there had been a meeting was not permitted to become public.” This Georgia genesis underscores how Southern geography inadvertently cradled a national transformation.

Ramifications: Stability, Power, and Enduring Controversies

The Federal Reserve’s creation marked a seismic shift. Initially, it achieved its core aims: providing elastic currency through open market operations, discount lending, and reserve requirements. The Fed helped finance World War I by buying government bonds, stabilizing the economy during the 1920s boom.

Post-1929 Crash, however, its tight money policies exacerbated the Great Depression, leading to reforms like the Banking Act of 1935, which centralized power in the Board of Governors.

Long-term effects have been profound. The Fed’s dual mandate—maximizing employment and stabilizing prices—has guided monetary policy through crises like the 2008 financial meltdown and the COVID-19 pandemic, where it injected trillions in liquidity.

Economically, it ended recurrent panics, fostered growth, and enabled fiat currency after Nixon’s 1971 gold standard abandonment. Atlanta’s Fed branch, for instance, oversees payments and research for the Southeast, contributing to regional stability.

Yet, ramifications include sharp criticisms. Detractors argue the Fed enables inflation—eroding purchasing power since 1913, with the dollar losing over 96% of its value. Conspiracy theories abound, from G. Edward Griffin’s The Creature from Jekyll Island portraying it as a cartel enriching elites, to claims it perpetuates debt-based money.

Since that secret Georgia meeting:

- The dollar has lost 97% of its purchasing power. A 1913 dollar is worth less than 3 cents today.

- The Fed has financed every major war – and every major bubble – of the last 100 years.

- It has the unchecked power to print trillions out of thin air, making the rich richer while your paycheck buys less every year.

- It operates in near-total secrecy. Even Congress is forbidden from auditing its most critical decisions.

Politically, it has fueled debates over independence; Presidents like Trump have pressured it for lower rates, while audits (like Ron Paul’s “Audit the Fed” push) seek transparency.

In Georgia, the Fed’s legacy is tangible. Our state’s economy, from agriculture to fintech hubs in Atlanta, benefits from stable credit, but rural areas still grapple with unequal access.

Final Word

As we mark over a century since that fateful meeting, the Fed remains a double-edged sword: a guardian against chaos or an unchecked behemoth?

This unflinching look reminds us that history’s turning points often hide in plain sight—or, in this case, behind Georgia’s coastal dunes. For better or worse, the Federal Reserve’s roots run deep in our soil, influencing every dollar we earn and spend.

More From AtlantaFi.com:

-

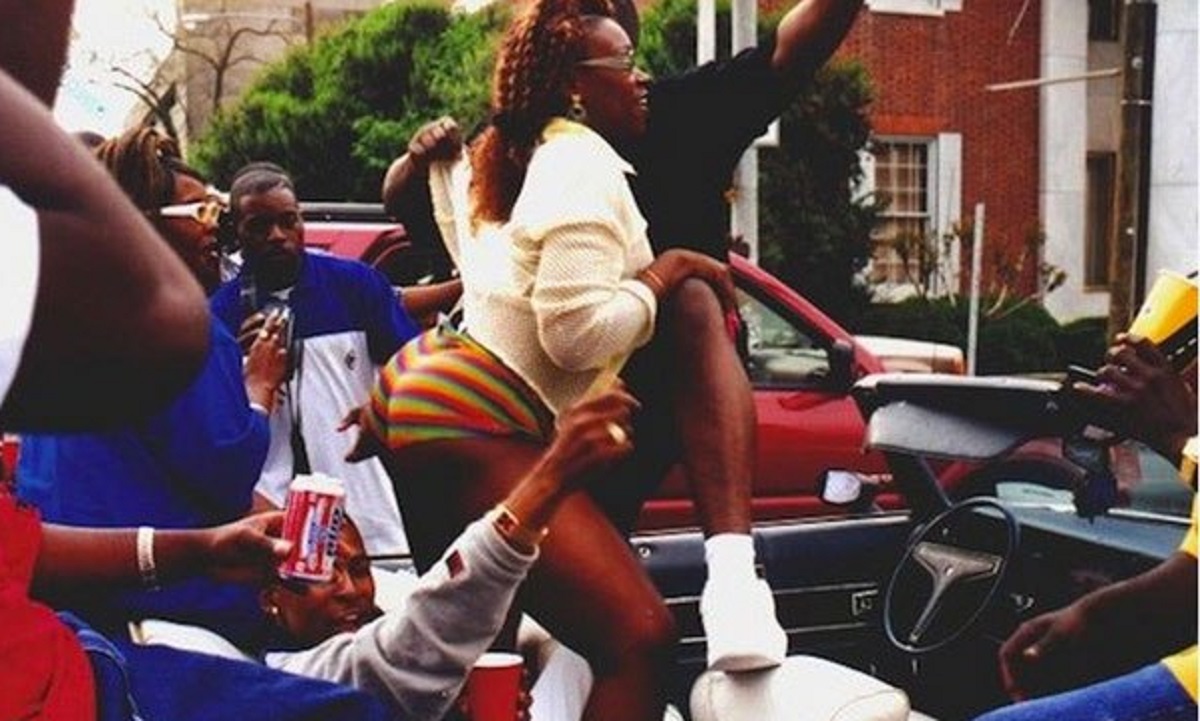

With the making of a new Hulu documentary about Freaknik, the roving street party is getting more attention than it has in 30 years.

Freaknik — Freaknik (/ˈfriːknɪk/; originally Freaknic) is a 1980s-90s era annual spring break party for black college students that grew into one of the largest rolling street parties in America.

The documentary is set to be released in the coming weeks, but there’s a lot to unpack.

Freaknik: How It Began

This article will provide an unofficial history of Freaknik, the famous and infamous rolling party that snared Atlanta traffic and turned highways into parking lots and dance floors.

The origins of what would become Freaknik can be traced to 1983, when dance clubs made up of students from the Atlanta University Center began throwing parties. This was the height of the pop-locking craze and a few years after aspiring filmmaker Spike Lee had left the AU Center’s Morehouse College.

One group in particular, the D.C. Metro Club, conceived of a party coinciding with spring break in April. It’s name was “Freaknic,” a play on the words “freak” and “picnic.”

Party flyer from the early 1980s.

The president of the D.C. Metro Club, Schuyla Goodson, is credited with coming up with the term “Freaknik” on the grounds of Spelman College.

There is some debate over where the inaugural Freaknic was held, but many say it was at John A. White Park near the AU Center.

The first “Freaknic” party was attended by around 150 people and became an annual event, but the D.C. Metro Club got in trouble with Spelman College. Then-President Johnetta B. Cole banned the group for the legal risk that Freaknic posed as the parties grew larger and larger.

Through the late 1980s, AU Center officials tried to sanitize the event, renaming it “Black College Spring Break,” with an obvious appeal to HBCUs in the MEAC, SWAC and various small black colleges and universities scattered around the South.

As the number of visitors to Atlanta began to swell each year, the behavior of the attendees began to worsen. As does everything in the South, the discussion began to take on racial undertones and then overtones.

“Most of the white establishment wanted Freaknik to end pronto,” said Fred Richard, a Grambling State University alumni, who now lives in suburban Atlanta after going to grad school at Clark. “We partied so hard in Atlanta because we didn’t want to go to Daytona Beach; we wanted to have fun here like they were doing in Florida.”

Race Becomes A Factor

Atlanta’s African-American lawmakers, all the way from council-men and -women to others in high positions around the city’s mayor, tried to balance their obligations to keep law and order by extending a welcome mat to the party-goers, which were overwhelmingly black.

But news broadcasts would often lead with the arrests and images of rowdy behavior from the crowds of students in town for the raucous weekend. Resentment from residents in Atlanta’s top neighborhoods slowly began to boil as negative news reports about Freaknik began to circulate.

The issue was illustrated best by then-Councilwoman Carolyn Long Banks, who told the Times, “There is a fear of the congregating of more than one or two black people in any given area. It has become a racial issue for some of the neighborhoods. These kids are the black cream of the crop, and if they are not treated well, there is little hope for the rest of us.”

In the early 1990s, the AU Center dance clubs, fraternities and sororities all tried to milquetoast the “Freaknik” name — downplay it and rebrand it “Freedom Fest was one attempt) — but it was too late. College officials, engaged in feeble attempts to refocus the then-highly sexualized party weekend, tried bonding it to a job fair, step shows and other collegiate events, but to no avail.

Music And More Began To Change

In 1990 and 1991, Freaknik was still just another black spring break function, the likes of which students at Winston-Salem and Norfolk, Virginia, were used to.But by the end of 1991, a wave of misogyny would sweep through rap and hip-hop music. Instead of the conscious, pro-black vibes that came to characterize much of the popular music, the tunes turned to darker themes, often fueled by weed smoke.“The music definitely played a role in how people started acting,” Wilson said. “Instead of bumping Public Enemy or listening to some words by Sistah Soulja, gangsta rap exploded. Everybody was on that NWA, West Coast, all that stuff.”But it wasn’t just gangsta rap. Florida’s Miami bass, New York’s lyrical hip-hop and the South’s own SouthernPlayalistic vibes were all contributing. You can’t have a party without the music.Another culprit was the mob mentality: A common scene for Freaknik was to see a jam -packed street with people on the hoods of the cars and loud music. Women would be dancing on the cars or next to one and they would be surrounded by ogling and touchy-feely men with video cameras.“In a lot of ways, what set Freaknik off in the early 1990s was the videotape footage. Like the videotape beating of Rodney King that set off riots, when people from all these different cities came back home and showed their friends the video footage of Freaknik, it exploded.”According to media estimates, about 100,000 people attended Freaknik in 1993. The next year, that numbered had doubled to 200,000 although arrests were cut in half.As Olympics Neared, Atlanta Wrestled With Its Image

At the crux of many civic debates, was this question: What kind of city was Atlanta trying to be? A party city or one that was brand-safe for big business?

“You have to understand,” said Tony Robinson, a barber from Atlanta, who went to Clark Atlanta in the late 1980s. “In the early 1990s, Atlanta was in the midst of remaking itself for the Olympics.”

In 1994 and 1995, the city was being flooded with new money and was trying to put on its best face. But this rolling black street party would churn through every year and make national headlines for all the wrong reasons.A New York Times article from that time says, “Young people showing off their late-model luxury cars in caravans tied up major arteries for about five miles north of downtown. But the police managed to channel most of the impromptu motorcades out of residential areas. Mayor Campbell acknowledged that “there were no streets which could contain the cars and the young people’s determination to stay in their cars and to see and be seen.”When visitors began to pour into Lenox Square, the mall of Atlanta’s wealthy, the affluent residents began to complain about the traffic outside the structure. Instead of a place to shop, the weekend brought thousands of people-watchers and rowdy behavior.Atlanta’s City Council and Mayor Bill Campbell, who was elected in 1994, began to get criticized for allowing the city to be overrun with “hoodlums” and party-goers who would go inside stores to gaze but wouldn’t shop.Atlanta Mayor Bill Campbell in 1996.

Tug Of War: Atlanta Politics Meets Freaknik

The city’s white business leaders began to push for an all-out ban on Freaknik, putting tremendous pressure on Atlanta’s black leadership, which was starting to feel the heat.In front of the microphones, Atlanta’s black leaders were politically correct when asked questions about Freaknik and public safety.“We welcome anybody coming to this event who is law-abiding,” said Atlanta Police Chief Beverly Harvard. “We will not tolerate the violation of this city.”

Privately many of them wondered how long they could last as political piñatas.

“If our event goes poorly as a result of the Freaknik crowd, it would seriously jeopardize my ability to come back,” Campbell said in March 1995, one month before the event. “So Atlanta does have a lot riding on the success of this.”

Freaknik: Business and Residential Resistance

One neighborhood, Inman Park, even sued the city to keep it off-limits from visitors. Spurred by Atlanta’s business elite, the City of Atlanta began to turn against Freaknik at least to some degree. Some Atlanta students said race was a major factor.Quoted by the Washington Post at the time, Samuel Bell Jr., who was student body president at Clark Atlanta University, said, “These students are, supposedly, the future leaders of our nation, and what are they saying, that we’re going to loot and pillage the village? It’s an atrocity.”The city responded by denying permits to party organizers and offering underwhelming support to the few activities that happened to be sponsored. Police officers blocked entry into whole neighborhoods and made some streets one ways around the AU Center.“Remember, this wasn’t Miami. This wasn’t Jacksonville or even Galveston, where there’s a beach. Atlanta is all asphault,” said Robinson. “Half of the city — and you know which half — just couldn’t understand what all these black people were doing down here.”Inside City Hall, leaders tried to soften the mayor’s stance, saying that the students should be welcomed by the city, but that their energy should be channeled into a more positive direction.C.T. Martin, an elder statesman on the city council, said then, “I understand the mayor’s predicament, but this is the home of Martin Luther King and six black institutions of higher learning, and we owe it to the parents of these young people to cradle their children while they are here.”Atlanta Turns On Freaknik

“There is nothing for people to do,” Lori Dodson, a Spelman student at the time, told the Times. “We had events scheduled but we had to cancel them because of the city.”While there was sporadic violence connected to the event each year, Atlanta officials touted the success of letting students flock to the city, but kept them driving in circles by routing them to the highways and away from prestigious areas. Faced with no where to go, many revelers congregated in parking lots and just partied in their cars and on the streets.To save face, Atlanta officials stopped providing the press with crowd estimates, which would only fuel the naysayers. Still, the police would shut down around 200 blocks of city streets to curtail cruisers during the three-day weekend.“They tried to stop it before it got started,” Corey Griffin, a reveler from Dalton, Georgia, told the Times at the time. “I think it’s nice to come down here and spend some money. But I felt I was unwanted.”Soon Campbell and city officials made it ther mission to deny any permit associated with the words “Freaknik” or “Freaknic.”As the 1990s closed, Freaknik became a shadow of itself and all but died out except for the occasional brash party promoter.“Few issues in the city of Atlanta have been as divisive in the last 10 years,″ Campbell told the Associated Press in 1998. “It is a very difficult weekend even under the best of circumstances.″“In Atlanta, Freaknik became a curse word,” said Monica Wilson, who traveled to the annual party each year from 1993 to 1996 as a student at Southern University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.With no public safety support, sponsors or organizers, Freaknik, seen as a headless monster, began to unravel and die out.Final Word

What began as a party for collegians quickly morphed into a weekend of unabashed street partying. Among the city’s business leaders, the sentiment was that Atlanta was built for a lot of things, but it wasn’t built for that.Crowds particularly gathered around city landmarks like Underground Atlanta, Piedmont Park, Old National Highway, the AU Center and Peachtree Street, the city’s main vein.All but dead, now the name “Freaknik” still pops up every now and then, but it’s in reference to its heyday, circa 1994 and ’95. It is the party that time forgot. -

Atlanta, Georgia has been called the jewel of the Southeast. No wonder: Millions of people move to Georgia’s largest city every year. But do you ever find yourself wondering “what is Atlanta known for?”

It’s a fair question given the diverse transients that have come and made Atlanta home, bringing with them their own cultures, flavors and traditions.

The city, as a result, has become a hodge-podge of different styles and vibes. But it’s still Atlanta.

Atlanta was founded in December 1847 when Georgia officials decided to build a railroad to the Midwest. This terminus would soon become the ATL.

What Kind Of Food Is Atlanta Known For?

We get this all the time. Atlanta may have a Waffle House on every block, but there’s no one food group that the city can be associated with

When it comes to beverages, though, it’s pretty fair to say that sweet tea is the drink of choice.

Fried chicken may come to mind for most folks, but the fact of the matter is that most Southern cities and towns can stake a claim to fried yard bird.

And chicken and waffles is served at only a handful of restaurants here so that’s out of the question. Yep, sweet tea, on the other hand, is served in nearly every restaurant.

Want to know more about Alanta’s dining scene? Here are foods that Atlanta is know for around the world.

How Many Peachtree Streets Are In Atlanta?

If you’ve ever tried to navigate around Atlanta’s streets, one thing that can be as confusing is all get out is the number of Peachtree Streets, Avenues, Boulevards, etc., around the city.

At last count there were more than 70 streets with the “Peachtree” moniker in their names.

It also bears saying that Peachtree Street, Ave and Road are all the same depending on whether the stretch is zoned as residential, commercial and/or a mix of both. But in any event, when you’re in Atlanta, GPS is your friend! (But more on this later).

What Are Some Of The Most Iconic Atlanta Landmarks?

Underground Atlanta used to be the #1 place you’d bring a visitor but not this century! Now, some of the most iconic places are newer and more polished (although there are still a handful of older landmarks you still want to see).

Clermont Lounge

This place is an Atlanta institution of the adult variety, if you get what I mean. If you’re looking for elegance, this is the opposite.

But it has been a fixture on Ponce de Leon Avenue because the place has managed to stay open despite the ups and downs of “progress” all around it.

The Varsity

Situated on a plum plot of land in Midtown by the freeway, The Varsity has done for the chili dog what Waffle House has done for the waffle. The restaurant features a drive-in with car-side service, making it one of the last of its kind. The food is not the award variety, but it’s a must if you want to taste what Atlantans have been eating for nearly 100 years.

Centennial Olympic Park

Centennial Olympic Park is an oasis in the middle of downtown Atlanta. One of the lasting remnants of the Atlanta Olympics (which we’ll talk about later) is a beautiful greenspace that serves as the centerpiece of downtown Atlanta.

There are numerous places to take pictures and even a ferris wheel nearby.

Read up on some of Atlanta’s best parks.

Underground Atlanta

Go in the center of downtown and beneath the bustling streets of downtown Atlanta lies Underground Atlanta, a historic area that was once the city’s original street level. Today, it features shops, restaurants, and entertainment venues, offering a glimpse into Atlanta’s past.

Atlanta History: Events That Happened Here

Atlanta has been home to some of the most historic events in U.S. history. Here are some things that happened in Atlanta that you may not know about.

The Winecoff Hotel fire happened in Atlanta

The Dec. 7, 1946 fire at the Winecoff Hotel (now the Ellis hotel) in downtown Atlanta is the deadliest such blaze in U.S. history. 119 people died in the fire, which helped spark huge changes in U.S. building codes, most notably requiring mandating fire-resistant doors and firescapes.

Atlanta Child Murders

One of the darkest moments of the cities history was when a serial killer started exacting lives of young boys and girls around the city, many of them African-American.

While the case proved as controversial as the murders, Wayne Williams was convicted of the crime, which many believe was committed by someone else. Nevertheless, it is an historic event that happened.

The 1996 Olympics

The 1996 Olympics were the culmination of decades of goodwill and moving and shaking by the city’s powers that be. Although it was a triumphant moment when Muhammad Ali lit the torch, the event was also marred by an instance of domestic terrorism which took the form of the Olympic bombing.

Atlanta Is The Only U.S. City Destroyed In A War

During the Civil War in the spring of 1864, the Confederate Army of Tennessee, commanded by General Joseph E. Johnston, was holed up in Dalton, Georgia. The Union Army wanted to do something about it, amid other troublesome skirmishes taking place, so in early May, 1864, Union forces under Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman began the Atlanta Campaign, a “scorched earth” policy to burn the city to the ground. The basically uncontested “March to the Sea” would destroy a swatch of Georgia.

Atlanta Has More Pro Sports Teams Than You May Know

When you think of Atlanta, your mind may immediately focus on the Hawks, Braves or Falcons, but we’ve got more birds than that. Here are a number of professional teams that call Atlanta home:

Club Sport League Venue (capacity) Founded Moved to Atlanta Titles Atlanta Falcons Football NFL Mercedes-Benz Stadium (71,000) 1966 N/A 0 Atlanta Braves Baseball MLB Truist Park (41,500) 1871 1966 4 (1914, 1957, 1995, 2021) Atlanta Hawks Basketball NBA State Farm Arena (18,100) 1946 1968 1 (1958) Atlanta United FC Soccer MLS Mercedes-Benz Stadium (42,500) 2014 N/A 1 (2018) Atlanta Dream Basketball WNBA McCamish Pavilion (8,600) 2007 N/A 0 Atlanta Legends Football AAF Georgia State Stadium (24,333) 2018 N/A 0 Atlanta Is A Championship Sports Town

Photo credit: Major League Baseball The Atlanta Braves won the World Series in November 2021, breaking a more than two-decade drought.

Atlanta United, in just its second season, won the MLS Championship in 2018 with a commanding 2-0 win over Colorado. Atlanta United, which plays at the Mercedes-Benz Stadium set attendance records for the second straight year on the way to their title. Before Atlanta United’s victory, the city had gone 25 years since a title in a major sport. The Atlanta Falcons came the closest in 2017 before losing to the New England Patriots.

Atlanta Has The World’s Busiest Airport

More than 10 years running now (since 1998), Atlanta has had the world’s busiest airport. Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport, located on the line between College Park, Hapeville and Atlanta, attracts more traffic and has more airplane movements than any other airport in the world. You can also save money at Hartsfield if you strategize.

The airport is named after William B. Hartsfield, who founded the site on an abandoned racetrack, and Maynard Jackson, the first black mayor of Atlanta.

Coincidentally, Hartsfield is home to Delta Air Lines, one of the largest airlines in the world, and a major reason Atlanta is a traffic hub.

Atlanta Is Growing (And Growing)

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Atlanta experienced the third-highest population gain of any metro area in the United States, behind the Texas cities of Dallas and Houston. Between 2016 and 2017, metro Atlanta gained nearly 90,000 new residents, bringing the total population in the region to an estimated 5.8 million people.

Here’s how many people live in Atlanta.

Atlanta Is The Birthplace of Martin Luther King Jr.

Photo credit: Yotuube.com While it is true that Birmingham, Alabama is the cradle of the civil rights movement, Atlanta is generally recognized as the birthplace of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., the movement’s most prominent leader.

Years before the tragic murder of his mother, Mrs. Alberta Williams King, MLK, along with a number of key leaders like Andrew Young, Hosea Williams and more, roused the nation to its senses by pioneering the nonviolent protests that finally toppled segregation across the nation. King was born in Atlanta in the Auburn Avenue neighborhood in 1929. Today that site has been recognized as historic and is just a few blocks from the King Center.

Coca-Cola Was Born In Atlanta

If you like Coca-Cola, you are enjoying a taste of Atlanta with every sip. The soft drink’s long history began in 1886 when an Atlanta pharmacist, Dr. John S. Pemberton, created a flavored syrup, took it to his neighborhood pharmacy, where it was mixed with carbonated water and deemed “excellent” by those who sampled it. Dr. Pemberton’s partner and bookkeeper, Frank M. Robinson, is credited with naming the beverage “Coca Cola.”

There Are 60+ Streets Named ‘Peachtree’

If you’re trying to find your way around Atlanta, “Peachtree” just won’t cut it. There are more than 60 streets with a variation of Peachtree in their names, with some of them as far as 30 minutes away from downtown Atlanta.

Atlanta Is The New Hollywood

Atlanta houses the No. 1 film industry in the United States, having surpassed Hollywood in 2016. The metro Atlanta region began offering generous tax incentives in 2002 to lure movie producers. Today, Georgia has a $90 billion movie industry. See what’ movies are filming in Atlanta.

Atlanta Is Not The Strip Club Capital Of The U.S.

Photo credit: Instagram Contrary to popular belief Atlanta is not the strip club capital of the United States, that distinction is Portland, Oregon. Still, Atlanta’s many strip clubs make it No. 1 in the South. Here are the best strip clubs in Atlanta.

Final Word

Atlanta has paid a pivotal role in the South as well as the larger United States. The city is known for more than its hospitality and sweet tea. There’s sports, there’s good restaurants and there’s the booming real estate market.

Are you a beer drinker? You also may want to visit to a craft brewery in the city.

Check out these events in Atlanta today and this week and this weekend:

Here are more articles from AtlantaFi.com:

-

“War is hell.” That familiar phrase was reportedly first uttered by Union General Tecumseh Sherman during the Civil War. Sherman commanded more than 100,000 troops as destroyed the American South town by town in the infamous “March to the Sea.”

Did You Know About The Slave Auction House In Atlanta?

One of the cities in his wake was Atlanta, then a teetering rail town. There are photographs that exist of much of the carnage, thanks to official Union photographer George N. Barnard, who was embedded with the soldiers.

In 1866, Barnard published one of the most important war photography projects of all time, “Photographic Views of Sherman’s Campaign.”

Much of Atlanta’s landscape was part of Sherman’s activities. As Georgia Tech’s historical account observes, “In anticipation of advancing Union troops in the summer of 1864, several forts were built on what is now Georgia Tech land. Seen as strategically high ground, land along the southern edge of campus was cleared and fortified by the Confederacy to prevent direct frontal attacks on the city.”

One of the more iconic pictures taken during Sherman’s invasion of Atlanta shows a structure on Whitehall Street used to hold slave auctions all but abandoned. Whitehall Street today is in the middle of a den of old, abandoned buildings, open and wild fields and liquor stores.

Atlanta has a lot of inspirational people and AtlantaFi.com is going to introduce you to many of them as well as cool places to go, great restaurants and other ATL happenings.

Got an event or know of something opening in and around Atlanta? Holla: CJ@AtlantaFi.com. See what’s poppin’ in the ATL! Subscribe to our news alerts here, follow us on Twitter and like us on Facebook.

-

Much is made about the guitar work of superstar Jimmy Hendrix, whose rendition of the “Star Spangled Banner” forever altered the anthem in the minds of countless baby boomers.

The performance was cemented at Woodstock, the 1969 music festival in upstate New York.

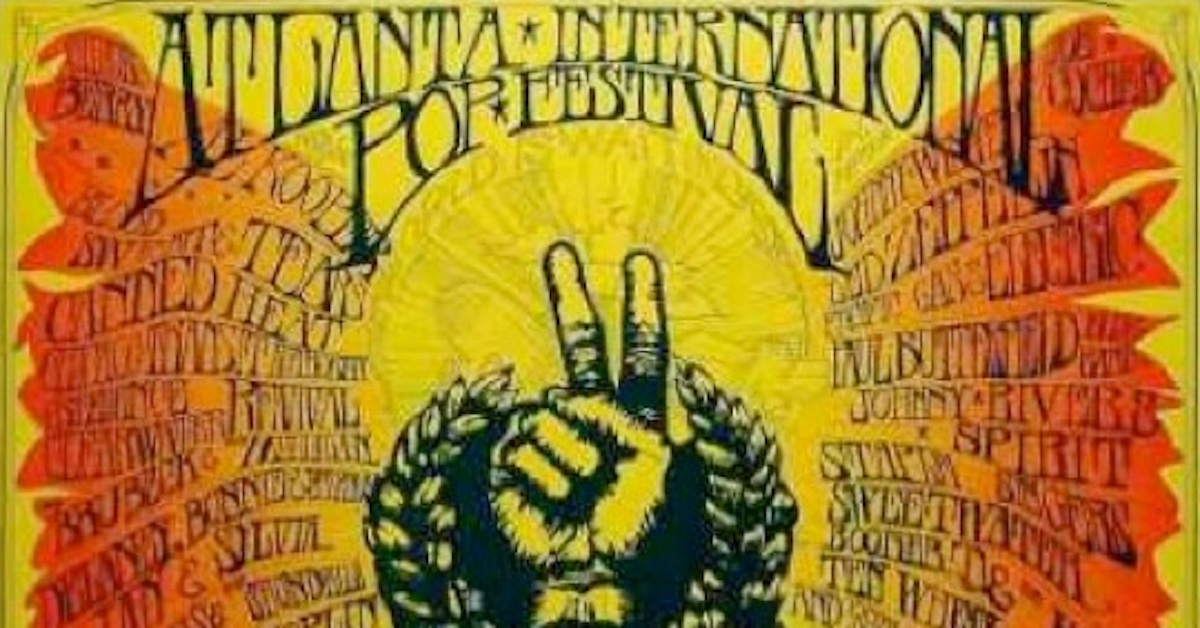

Remembering The Atlanta International Pop Festival

More than a month before more than 400,000 hippies, college students and lost souls traveled to a remote gathering space up north, Atlanta hosted an event that featured many of the same artists.

When Was The Atlanta International Pop Festival?

The official name of Woodstock was “An Aquarian Exposition: 3 Days of Peace & Music,” in ATL, The rock festival was held at the Atlanta International Raceway in Hampton, home of the Atlanta Motor Speedway, on July 4th, 1969.

According to Birmingham Weekly, “The bill was wildly eclectic, from mainstream jazz with Dave Brubeck to first generation rock with Chuck Berry; from sweet soul by the Staple Singers and Booker T to the blues of Canned Heat and Paul Butterfield; from the folk of Ian and Sylvia to the cataclysm of Led Zeppelin. As an intrepid band of explorers from Alabama arrived at the outskirts of Hampton prior to the show amid a stupendous traffic jam, it was clear that word-of-mouth had drawn the crowd Cooley sought.”

Cooley would go on to apologetically host a concert the following Monday in Atlanta’s Piedmont Park, embarrassed that he’d made a $12,000 profit at the pop fest. “You have to understand the context,” Cooley told Atlanta Magazine. “It was the height of the Vietnam War, and Lester Maddox was governor. I wanted to do something that would make people where I lived understand that we could change.”

There are so many Atlanta events popping off every week it’s hard to keep up with it all. That’s why I suggest you subscribe to AtlantaFi.com to get all the freshest gatherings, Atlanta happenings, parties and more delivered to your inbox.

Things to do in Atlanta on a weekly basis can range from going golfing mid-week to checking out the latest restaurant openings. At AtlantaFi.com, we curate the city for you!

Read more AtlantaFi.com stories:

Add as a preferred source on Google

×