In the heart of downtown Atlanta, at the corner of Peachtree and Ellis streets, stands a 15-story building that has borne witness to both glamour and unimaginable horror.

Now known as the Ellis Hotel, this structure was once the Winecoff Hotel – a beacon of early 20th-century luxury that became the site of the deadliest hotel fire in U.S. history on December 7, 1946.

Nearly 79 years later, the tragedy continues to shape fire safety standards nationwide and serves as a somber reminder of how quickly complacency can turn deadly.

The Winecoff Hotel: A History

In the early 1900s, downtown Atlanta pulsed with post-Reconstruction energy. Peachtree Street, the city’s grand artery, was transforming from a dusty thoroughfare into a commercial powerhouse.

The area around what would become 176 Peachtree lay just north of the Fairlie-Poplar Historic District, a hub of late-19th-century brick buildings housing banks, shops, and offices.

Pioneer hotel builder William F. Winecoff envisioned a luxurious retreat for Atlanta’s elite.

A ‘Fireproof’ Icon Rises in Atlanta

Opened in 1913, the Winecoff Hotel was designed by renowned architect William Lee Stoddart and quickly established itself as one of Atlanta’s tallest and most prestigious buildings.

Boasting 15 stories and a steel-frame construction clad in brick and terra cotta, it was marketed aggressively as “absolutely fireproof.”

This claim stemmed from its non-combustible exterior and structural materials, which met the building codes of the era. On a compact lot of less than 5,000 square feet, the hotel was exempt from requirements for multiple stairways, fire escapes, or sprinklers – a loophole that would prove catastrophic.

The Winecoff catered to travelers, holiday shoppers, and locals drawn to downtown Atlanta’s vibrant scene.

Its location near department stores like Davison’s and the Loew’s Grand Theatre – where Disney’s Song of the South was screening – made it a hub during the post-World War II boom.

Guests included families, businessmen, and even the hotel’s founders, W. Frank Winecoff and his wife Grace, who resided in a penthouse apartment.

With only one central stairway, two elevators, and no automatic alarms or suppression systems, the hotel relied on its “fireproof” reputation.

Interior finishes – wallpaper, carpets, and furnishings – were highly flammable, but this went largely unquestioned in an era before widespread fire safety reforms.

The Night the Flames Consumed Everything

The fire ignited around 3:15 a.m. on a chilly Saturday, December 7, 1946, likely on the third floor in a hallway mattress.

Theories abound: a discarded cigarette, electrical fault, or even arson tied to a late-night card game. Whatever the spark, the blaze spread with terrifying speed.

The open stairwell acted like a chimney, funneling superheated gases and smoke upward through the building’s core.

Of the 304 guests asleep that night, panic erupted as corridors filled with choking smoke.

Many were in town for Christmas shopping or the YMCA Youth Assembly at the state Capitol – including 30 of Georgia’s brightest high school students.

Screams echoed down Peachtree Street as trapped occupants smashed windows and hurled mattresses in desperate bids for survival.

Atlanta Fire Department engines arrived within minutes, mustering 385 firefighters, 22 engines, and 11 ladders.

But the hotel’s height outstripped their equipment; aerial ladders reached only the eighth floor. Rescuers extended ladders from the adjacent Mortgage Guaranty Building, forming human chains and using nets to catch jumpers.

Bystanders, including off-duty soldiers, held nets as bodies plummeted – some missing by inches and crashing onto marquees or pavement.

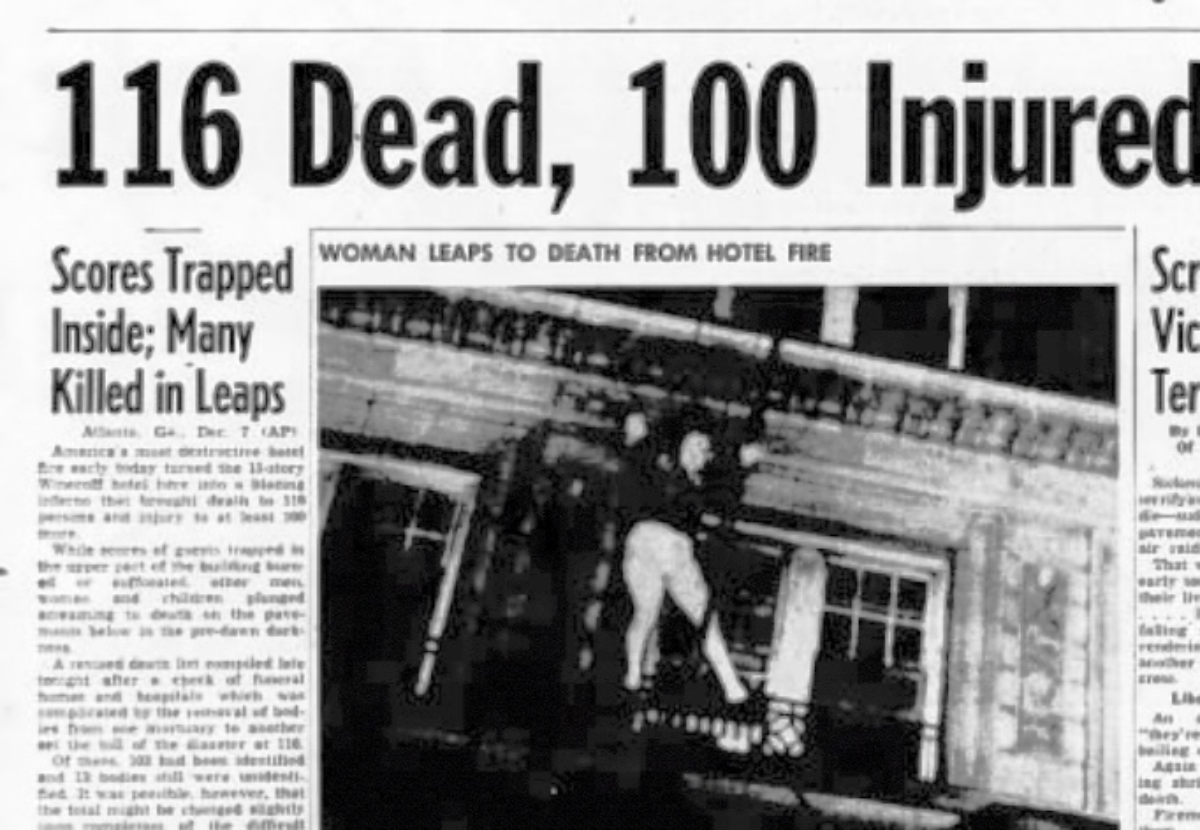

Amateur photographer Arnold Hardy captured the chaos, snapping a Pulitzer Prize-winning image of a woman mid-fall. Firefighters battled for over two hours in freezing temperatures, rescuing about 120 uninjured but forever scarred.

The Night That Changed Everything

At 24, Hardy was returning home around 3:30 a.m. from a date at a downtown dance hall. Hearing fire sirens, he phoned the station and learned of the blaze at the Winecoff Hotel on Peachtree Street.

Grabbing his camera and five flashbulbs, he cabbed to the scene—the first photographer there. In the pitch-black frenzy, guests leaped from windows or dangled from bedsheet ropes.

Hardy offered aid to firefighters, who declined, so he focused his lens.

One bulb exploded in the cold; he fired off shots of horrified faces in windows.

With his last bulb, he aimed upward, timing a shutter release to capture a woman plummeting feet-first from the 11th floor. Her skirt billowed, revealing white underpants against the flaming facade—a raw, unflinching image titled “Death Leap From Blazing Hotel.”

Developing the film in Tech’s darkroom by 6 a.m., Hardy sold three photos to the Associated Press for $300 (about $4,800 today).

The AP wired it nationwide; it graced front pages and magazine covers, humanizing the Winecoff’s 119 deaths.

Initial reports claimed the woman died on impact. In reality, she was Daisy McCumber, a 41-year-old from Vidalia, Georgia, who survived with shattered bones, internal injuries, and eventual leg amputation.

Embarrassed by the exposure, McCumber avoided publicity until her 1992 death.

In 1947, Hardy’s photo earned the Pulitzer—the first for an amateur—plus five other top awards.

A Devastating Toll: 119 Lives Lost

By dawn, the fire had claimed 119 lives – 41 from burns, 32 from suffocation, and 26 from falls or jumps. Another 65 were injured.

Among the dead: the Winecoffs themselves, suffocated in their penthouse; 17-year-old Christine Adams Hinson, a Youth Assembly delegate; and former Miss Atlanta runner-up Margaret Wilson Nichols, who fell from the seventh floor.

Survivors recounted harrowing escapes: tying bedsheets into ropes, crawling through smoke-filled halls, or leaping into nets.

One intoxicated guest slept through the ordeal unharmed. Firefighter R.B. Sprayberry, who helped recover bodies, never spoke of the night again.

Aftermath: A Nation Awakens to Fire Risks

The Winecoff disaster, coming months after deadly blazes in Chicago and Dubuque, shocked America.

The president convened a national fire safety conference, and cities rushed to update codes.

Georgia enacted a building exit law requiring multiple egress routes, effective on the fire’s first anniversary.

Nationally, standards mandated sprinklers, fire-resistant doors, alarms, and retrofits for older buildings – debates once dismissed as unconstitutional takings.

The hotel reopened in 1951 after renovations but struggled, closing in the 1980s.

It sat vacant until 2007, when a $23 million rehab transformed it into the boutique Ellis Hotel – complete with sprinklers, modern alarms, and fireproof materials. Today, it honors the past with a historical marker dedicating the site to victims, survivors, and rescuers.

Legacy: Safer Skies in the City Too Busy to Hate

The Winecoff fire remains the deadliest hotel blaze in U.S. history, a testament to its profound impact. It spurred the professionalization of firefighting, statewide training requirements, and innovations like self-closing doors.

Atlanta’s skyline, now dotted with high-rises, owes its safety to those lost that night.

What Is the Site of the Winecoff Hotel Today?

As Atlanta grows, the Ellis Hotel stands as a resilient symbol.

Visitors can stay in rooms with views of Peachtree, but the echoes of 1946 linger – urging vigilance.

“We were all spared for a reason,” survivors have said. In a city that rose from ashes before, the Winecoff reminds us: Fireproof is a promise only as strong as the precautions behind it.

For more on Atlanta’s historic fires, visit the Georgia Historical Society marker at 176 Peachtree St. NE.