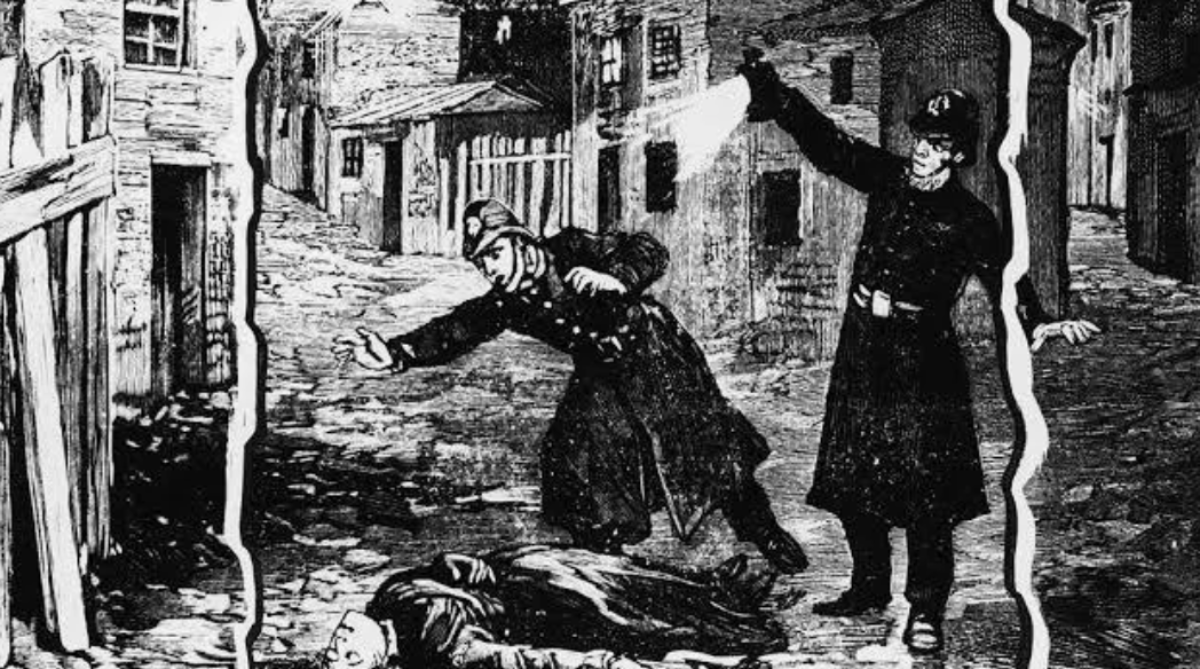

In the annals of Atlanta’s dark history, few chapters are as chilling and unresolved as the saga of the Atlanta Ripper.

Between 1911 and 1912, with possible extensions from as early as 1909 to 1915 or even later, a shadowy figure—or perhaps multiple perpetrators—stalked the streets of the city’s Old Fourth Ward and surrounding areas, preying on young Black women.

Terror in the Shadows of Early 20th-Century Atlanta

This series of brutal murders, often compared to the infamous Jack the Ripper killings in London just two decades prior, left at least 20 to 24 victims in its wake and instilled fear in Atlanta’s Black communities during an era already fraught with racial tension.

The Atlanta Ripper’s crimes remain one of the city’s most infamous unsolved cases, a stark reminder of the vulnerabilities faced by marginalized groups in the Jim Crow South.

Drawing from historical records, newspaper archives, and scholarly accounts, this article revisits the timeline, victims, investigation, and lingering mysteries surrounding these heinous acts.

Historical Context: A City on Edge

The murders unfolded against the backdrop of a deeply divided Atlanta. Just five years earlier, in 1906, the city had endured a horrific race riot that claimed the lives of 25 to 40 Black residents and devastated Black-owned businesses.

Racial tensions simmered, with segregation laws enforcing stark inequalities.

The Old Fourth Ward, a poor and dimly lit working-class neighborhood, became the primary hunting ground for the killer.

Many victims were young Black or mixed-race women employed as domestics, laundresses, cooks, or seamstresses, often walking home alone at night after long days serving white households.

As historian Jeffery Wells notes in his book The Atlanta Ripper: The Unsolved Case of the Gate City’s Most Infamous Murders, “We had a serial killing episode here in Atlanta in the early 1900s… At a time when the African American population in Atlanta was already nervous due to the growing racial tension, the stories of the atrocities committed by the infamous Jack the Ripper in London were still fresh on everyone’s mind.”

This context amplified the panic, as whispers of a “Black Jack the Ripper” spread through newspapers like The Atlanta Journal and The Atlanta Constitution.

The Murders: A Pattern of Brutality

The killings typically occurred on weekends, under the cover of darkness in unlit alleys, wooded areas, or near railroad tracks.

Victims suffered debilitating head wounds from blunt objects like bricks, rocks, or train coupling pins, followed by slashed or slit throats.

Some bodies were mutilated further—stabbed, disemboweled, or even set on fire—and shoes were often removed or cut off, with personal items like hair combs scattered nearby.

The first widely attributed murder was that of Maggie Brooks, 23, found on October 3, 1910, with a fractured skull near railroad tracks.

However, some accounts trace the spree back to Della Reid in April 1909, discovered in a trash pile.

The pace quickened in 1911:

- January 22, 1911: Rosa Trice, 35, a laundress, found with a crushed skull and slashed throat after being dragged from the street.

- May 1911: Mary “Belle” Walker and Addie Watts, both with throats slashed; Watts, 22, was struck with a brick and pin.

- July 1, 1911: Lena Sharpe killed; her daughter Emma Lou survived a stabbing and described the attacker as a tall, slender Black man in a broad-brimmed hat.

- July 11, 1911: Sadie Holley, nearly decapitated with a head fracture.

- August 31, 1911: Mary Ann Duncan, throat slit between railroad tracks.

Other victims included Eva Florence, Minnie Wise, Mary Putnam (whose heart was cut out), and Laura Blackwell in 1917, whose body was burned. By some counts, unnamed victims pushed the toll higher, including a 15-year-old girl near the Chattahoochee River.

The Investigation: Bias and Dead Ends

Atlanta police were overwhelmed, lacking modern forensic tools and facing a surge in other crimes.

Racial prejudice played a significant role; officials often dismissed the killings as “drunken arguments” or “Saturday night violence” in Black neighborhoods, with one judge claiming there was “no such thing as a Black Jack the Ripper.”

Community leaders like Reverend Henry Hugh Proctor advocated for Black detectives to build trust and gather information, even holding meetings to encourage cooperation.

A $25 reward was offered after Sharpe’s murder, and Mayor James G. Woodward intensified efforts amid business concerns over the city’s reputation. atlanta.capitalbnews.org +1 Threatening notes signed “Jack the Ripper” appeared in 1914, warning of more killings.

Despite this, the white press often blamed victims or alcohol, while Black communities lived in fear.

Suspects and Arrests: No Closure

Several men were arrested, but none were convicted for the full series:

- Rosa Trice’s husband was briefly held but released.

- Henry Huff, linked to Sadie Holley via bloody clothes and scratches, was indicted but acquitted as killings continued.

- Todd Henderson was identified by Emma Lou Sharpe and seen near crime scenes but maintained innocence and was not convicted.

- Henry Brown, arrested for Eva Florence’s murder with bloody clothing, confessed under duress but was acquitted.

- John Brown was convicted for Laura Blackwell’s 1917 axe murder, possibly linked to others involving fire.

Some husbands or partners, like those of Lucinda McNeal and Ida Ferguson, received life sentences amid doubts of fairness.

Historians debate whether one killer, copycats, or unrelated domestic violence accounted for the deaths.

Legacy: Forgotten Victims and Enduring Questions

Over a century later, the Atlanta Ripper case remains unsolved, its victims largely forgotten without memorials or markers.

As one account poignantly states, “Their lives and their deaths were shrouded in neglect, buried by indifference, and disappeared from collective memory.”

The murders predate the more infamous Atlanta Child Murders by decades, yet they highlight persistent issues of racial injustice in criminal investigations.

Today, researchers like Wells and bloggers reconstructing the cases from archives keep the story alive, urging Atlantans to remember these women and the systemic failures that denied them justice.

In a city that has evolved dramatically, the Atlanta Ripper serves as a somber historical footnote, a call to confront the past’s shadows.